Welcome to Flash Pulp, episode four hundred and seven.

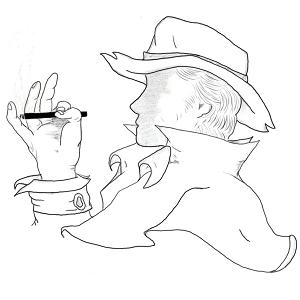

Tonight we present The Plague Wagon: a Blackhall Tale

[audio:http://traffic.libsyn.com/skinner/FlashPulp407.mp3]Download MP3

This week’s episodes are brought to you by Hugh J. O’Donnell’s The City

Flash Pulp is an experiment in broadcasting fresh pulp stories in the modern age – three to ten minutes of fiction brought to you Monday, Wednesday and Friday evenings.

Tonight we hear the whispered tale behind the black ambulance said to haunt the backroads of Capital County.

The Plague Wagon: a Blackhall Tale

Written by J.R.D. Skinner

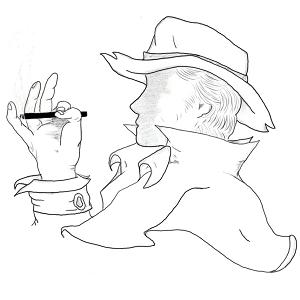

Art and Narration by Opopanax

and Audio produced by Jessica May

The trio stood before the Stunted Rooster, a public house not far north of the Capital City county line, and whispered to each other in the muted shouts of drunks stumbling home after quenching a Saturday night’s thirst.

In truth, Greene knew Cooper only because the man occasionally shoed his horses, and knew Rimbault not at all beyond his hasty self-introduction, but, as is often the case when confronted with the unexpected, the knot of men had become fast friends when brought up short on the Rooster’s veranda.

Shrugging at the merchant and blacksmith, Rimbault said, “I’ve heard of the thing – they call it the Plague Wagon. It’s said to be an ambulance of sorts, operated in service of the rich. The families on the west side of the city, their wealth knowing few bounds in regards to matters of beloved daughters and prodigal sons, apparently keep an enclave of witch doctors and wild-eyed surgeons sequestered along the coast, where the air itself also carries healing properties. This carriage is intended to ferry them across the highways and backroads with utmost speed and comfort.

Shrugging at the merchant and blacksmith, Rimbault said, “I’ve heard of the thing – they call it the Plague Wagon. It’s said to be an ambulance of sorts, operated in service of the rich. The families on the west side of the city, their wealth knowing few bounds in regards to matters of beloved daughters and prodigal sons, apparently keep an enclave of witch doctors and wild-eyed surgeons sequestered along the coast, where the air itself also carries healing properties. This carriage is intended to ferry them across the highways and backroads with utmost speed and comfort.

“Death the leveller indeed, but they do do their damndest to save themselves.”

There was little detail to remark upon in the coal-coloured ambulance, beyond the monochromatic theme of its jet-black curtains, wheels, and woodwork, yet it left its viewers with the unpleasant notion that there was no surface upon which to safely rest their eyes.

Having apparently oriented himself along the hand drawn map between his fingers, the driver again set the vehicle to forward.

The ebon Shire horses at its head gave their audience no attention as they passed.

“Yesss,” replied Cooper, his voice slow, as if speaking were helping draw out some memory from the depths of the recent alcoholic flood. “My boy, Billings, made mention of it after returning from a season in the lumber camps. As he related the tale, I seem to recall there is a unique strain of illness, highly deadly but easily transferred.

“Eventually nodules the size of an egg raising from their arms, and likely to burst at the slightest disturbance – it is the character of the contagion that any flesh thus touched then begins to boil in a similar nature, planting the illness anew.

“The weight of these tumors upon the chest and neck is the cause of death, as they inevitably smother the sufferer.”

“I pity for the passenger who must roll through these rough roads,” said Rimbault, his eyes still following the retreating wheels.

“I pity highwayman who attempts to waylay them,” snorted Cooper.

“If you must pity someone,” said Greene, “pity the driver, whose called upon to act as a sort of nurse in the transaction. It’s said to often be a poor fellow who is ill in some way himself, or someone so destitute that his family needs the money more than the man. I’ve heard each trip is well paid, but few hired survive more than three such expeditions.”

“Oh, where did you hear that?” asked Rimbault.

“Well, in all honesty, though I have enjoyed your renditions, I was given an evening’s dissertation on the topic by Bill Gelbert the milner, who said he’d heard it from a Smith. He told the tale as we both sheltered from an unexpected storm at the Ox and Mule. The thunder was heavy and it seemed an appropriate topic to fill the time between cups.”

“Funny,” said Cooper, ”I’d swear it was a Smith from which Billings took his account as well.”

There was a pause then, as the slow-trotting carriage rounded a distant corner.

Finally, in a too-loud tone, Rimbault announced, “plenty of Smiths in the world I suppose,” then lit his pipe. He did not add his following thought, which was that anyone wandering the countryside spreading stories should have thought to give a false name early in the proceeding.

His companions made no notice of the redness in his cheeks, nor the smirk on his lips, as they likely assumed both to be the result of ardent spirits.

The trio nodded in unison before exchanging goodnights, each now eager for the comforting warmth of their beds – and so it was that Thomas and Mairi Blackhall were able to undertake excursions, in the pleasance of each other’s company, without fear of catching the eye or interest of any who might wonder at the funerary rot that tainted the woman’s smiling face.

Flash Pulp is presented by https://www.skinner.fm, and is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Intro and outro work provided by Jay Langejans of The New Fiction Writers podcast.

Freesound.org credits:

Text and audio commentaries can be sent to comments@flashpulp.com – but be aware that it may appear in the FlashCast.

– and thanks to you, for reading. If you enjoyed the story, tell your friends.

At their center stood The Hag, an orb of light in one hand while the other rest on the torn and muck-covered jacket of her unchanged son’s shoulder. She was watching as each thrashing puppet climbed, in turn, atop the black-veiled platform their lifeless shoulders had carried across the face of Europe, over the salt, and through the dense wildwoods. There was smoke at each closing of the plush curtains, but no further evidence of its sacrifice’s passing.

At their center stood The Hag, an orb of light in one hand while the other rest on the torn and muck-covered jacket of her unchanged son’s shoulder. She was watching as each thrashing puppet climbed, in turn, atop the black-veiled platform their lifeless shoulders had carried across the face of Europe, over the salt, and through the dense wildwoods. There was smoke at each closing of the plush curtains, but no further evidence of its sacrifice’s passing. The old Roman roads were not so old when she began, and she slipped from the vineyards of the west to the steppes of the east just as a wind shifts and stirs at its own command.

The old Roman roads were not so old when she began, and she slipped from the vineyards of the west to the steppes of the east just as a wind shifts and stirs at its own command. Before long the thin-limbed lass whose wide brown eyes seemed to reflect an unflinching depth beyond a natural understanding was known simply as the Maiden.

Before long the thin-limbed lass whose wide brown eyes seemed to reflect an unflinching depth beyond a natural understanding was known simply as the Maiden. While he could, he said, “not at all – though they do worry over what your despair portends. If hearing the sobbing of a banshee signals death, what then, they must wonder, does it mean for one of your kind to weep so long and so deeply? No doubt they believe the entire township is on the verge of depopulation by plague.”

While he could, he said, “not at all – though they do worry over what your despair portends. If hearing the sobbing of a banshee signals death, what then, they must wonder, does it mean for one of your kind to weep so long and so deeply? No doubt they believe the entire township is on the verge of depopulation by plague.” “I think -” Blackhall began again, but Stroud again raised his finger, this time pulling a lanky parishioner by the name of Johan from the crowd.

“I think -” Blackhall began again, but Stroud again raised his finger, this time pulling a lanky parishioner by the name of Johan from the crowd. “I apologize,” said the prematurely-graying newcomer. “I’m Wyatt, the man who requested your presence. I would’ve joined you earlier, yet – well, you may’ve noted that business is sluggish, but what customers I receive depend on the regularity of my habits.

“I apologize,” said the prematurely-graying newcomer. “I’m Wyatt, the man who requested your presence. I would’ve joined you earlier, yet – well, you may’ve noted that business is sluggish, but what customers I receive depend on the regularity of my habits. The tone was too heavy, the setting too inevitable. He had killed before, and would again in self-defense, but his own time under the King’s command had long washed a taste for violence from his mouth.

The tone was too heavy, the setting too inevitable. He had killed before, and would again in self-defense, but his own time under the King’s command had long washed a taste for violence from his mouth. The master of the place had not noticed his intrusion. The old king stood before an immense fireplace, his tattered crimson robes dragging in the guttered ashes. His chest was largely bare, but he still wore the ringed metal of a swordsman’s armour.

The master of the place had not noticed his intrusion. The old king stood before an immense fireplace, his tattered crimson robes dragging in the guttered ashes. His chest was largely bare, but he still wore the ringed metal of a swordsman’s armour.